Blimp Lives!

A somewhat esoteric reading of the great film, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

A question people don’t often ask me but should, is: “Dave, what are your top 5 favorite movies?” It’s always a tricky business, and the answer tends to shift and cycle over time. Whatever it ends up being at a given moment, the list is probably a mercurial one: no Kubrick, no Scorsese, no Spielberg (though Raiders comes close). The Third Man definitely. Kieslowski definitely. Shoot the Piano Player probably. The Godfather has great staying power, as well as personal significance, having first seen it when I was about 7 or 8 (don’t ask). But it’s almost too enmeshed in America culture to really speak to me directly anymore. Maybe Once Upon a Time in the West, depending on how long it’s been since I’ve seen it?

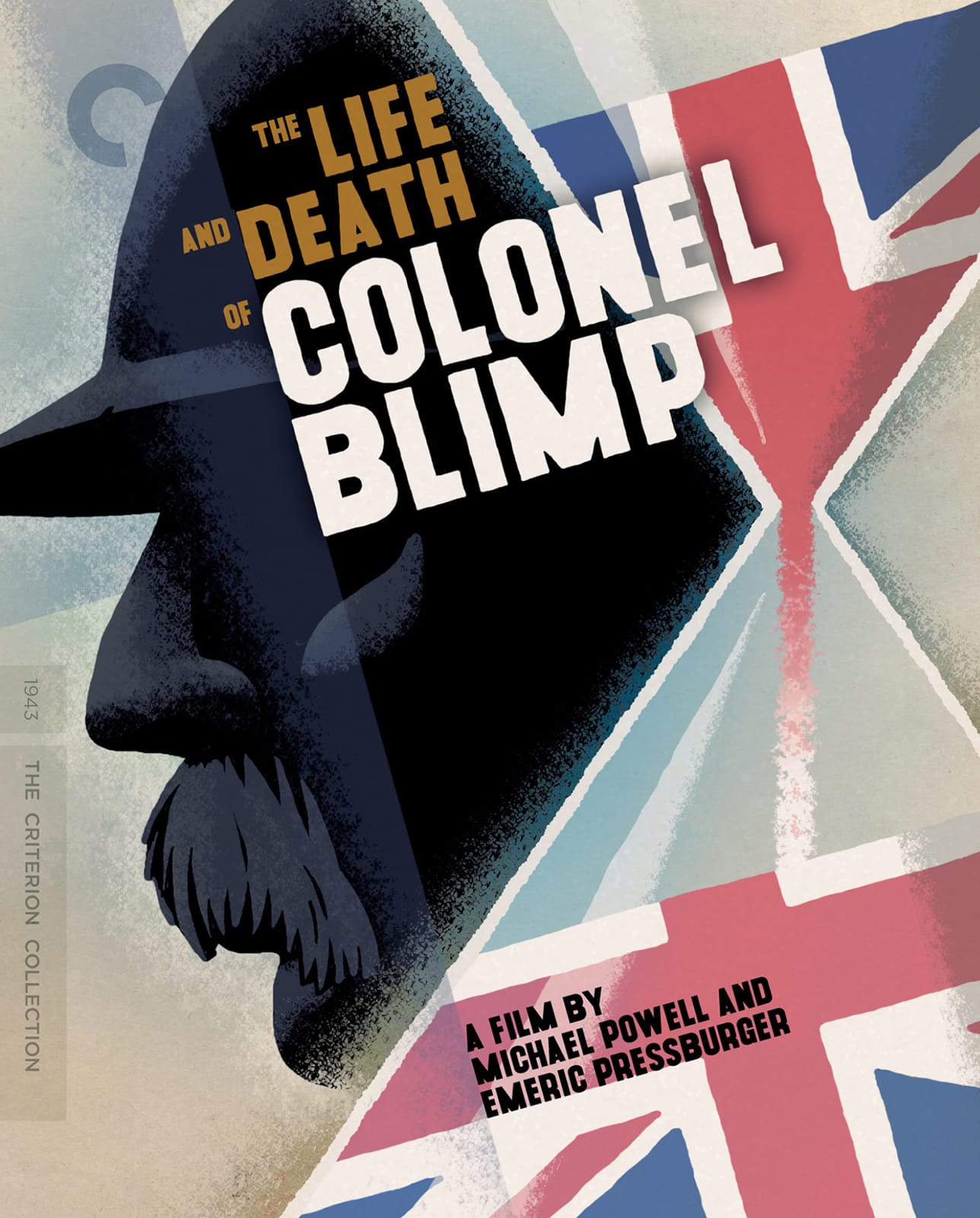

Others bob in and out, but one that has never left since I first saw it is also a film I too rarely see mentioned anywhere: The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp.

This is a movie I’ve never seen on TV, and I can’t recall ever encountering it in a movie store (perhaps one of the indie ones with their own “Criterion” sections that started to pop up around the tail end of the video era?). The first time I came across any reference to it at all was over twenty years ago in an intriguing writeup in Time Out’s (surprisingly excellent) Centenary list of 100 greatest films. There, at #23, lay the following description:

At a time when 'Blimpishness' in the high command was under suspicion as detrimental to the war effort, Powell and Pressburger gave us their own Blimp based on David Low's cartoon character - Major General Clive Wynne-Candy, VC - and back-track over his life, drawing us into sympathy with the prime virtues of honor and chivalry which have transformed him from dashing young spark of the Nineties into crusty old buffer of World War II. Roger Livesey gives us not just a great performance, but a man's whole life: losing his only love (Deborah Kerr) to the German officer (Walbrook) with whom he fought a duel in pre-First War Berlin, then becoming the latter's lifelong friend and protector. Like much of Powell and Pressburger's work, it is a salute to all that is paradoxical about the English; no one else has so well captured their romanticism banked down beneath emotional reticence and honor. And it is marked by an enormous generosity of spirit: in the history of the British cinema there is nothing to touch it.

I grokked about a third of that maybe, but something about it grabbed me, though it would be years before I finally managed to see it for myself.

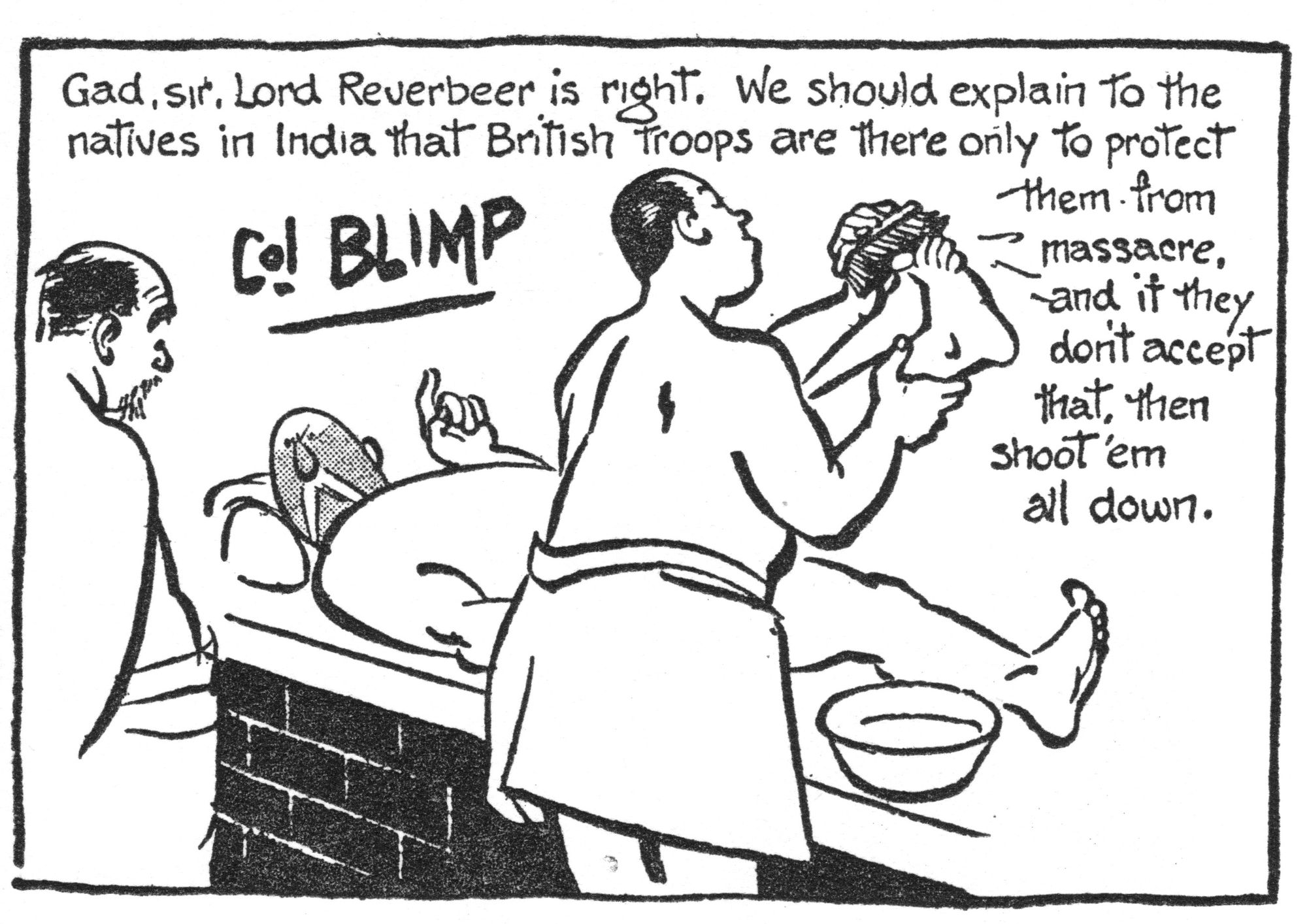

“Blimpishness” refers to something like: certain distinctively English qualities of jingoism and traditionalism that can be found in comic proportions in the older members of the middle class (both “Blimp” and “Blimpism” were common enough shorthand references at one time—Orwell makes frequent use of both in his essays that touch on the English character). Colonel Blimp himself was literally a character in a comic strip that ran in London’s Evening Standard back in the 1930s, who was prone to often self-contradictory outbursts of reactionary opinion.

But, like Socrates “become young and beautiful,” the film asks, in effect, what if Blimp were not only un-ridiculous but in fact heroic and honorable and decent—in short, the personification of what the British most esteem in themselves?

What It's About

The film is long, but the story is simple: the narration of Blimp’s (his actual name is the wonderfully British Clive Wynne-Candy, but we’ll just call him “Blimp” for brevity’s sake here) life from the early to the mid 20th-century, bookended by a framing device set during the height of the Second World War.

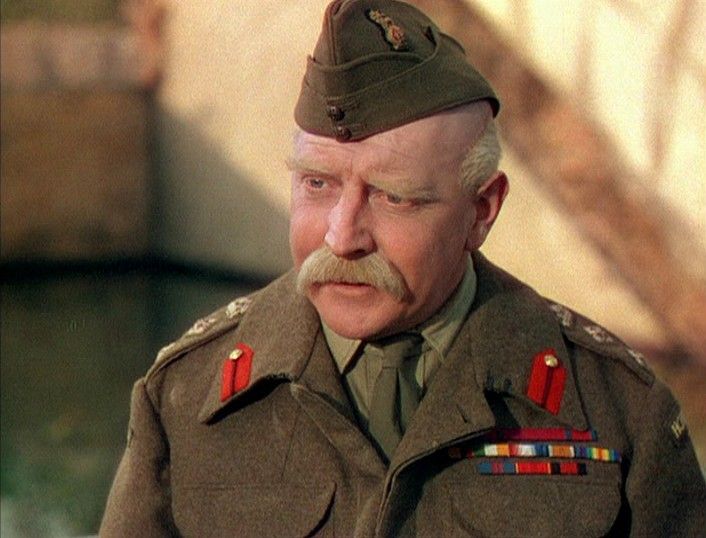

The film opens with Blimp as an old man, now a senior commander in the Home Guard in the early days of World War II. During a war game, he is captured in his favorite spot in the Turkish bath by younger officers who initiated their attack before the official start of the training exercises, on the logic that such is the way of modern warfare. Blimp is outraged by this display of Machiavellism, but he is also humiliated as he sees himself as antiquated in the eyes of the younger officers, prompting him to justify himself by telling his life story. The majority of the film then functions as an extended flashback, cutting to the years prior to the First World War.

There a younger Blimp fights and is wounded in a duel with a young German officer—the also wonderfully-named Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (hereafter, K-S), with whom he forms a lifelong friendship.

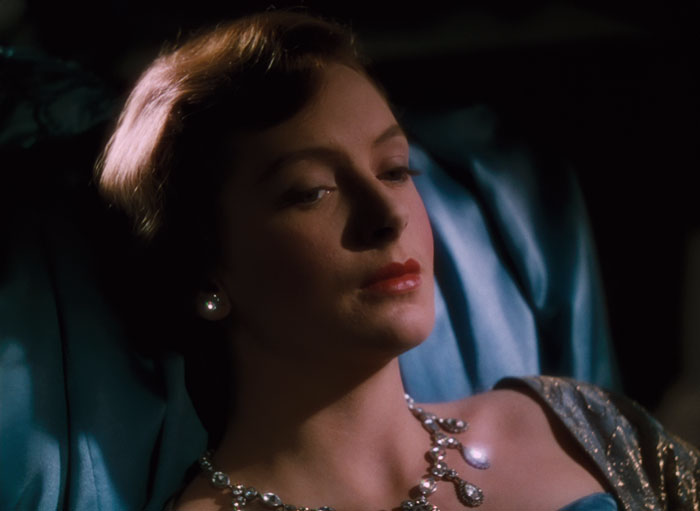

The two men become fast friends and both fall in love with the same Englishwoman. When K-S asks for Blimp’s assistance in proposing to her, Blimp chivalrously gives way. Much of the remainder of his life will be driven by his reticent attempt to manage this heartbreak, as he goes on to first marry and later hire as a personal assistant, respectively, different women who are dead ringers for the first one. Like Vertigo part of the plot turns on an unexpected resemblance between the different women (all played exquisitely by Deborah Kerr). But here it’s played as an indication of gentle and civilizing adoration rather than psychosexual obsession.

The subtlety with which they indicate the Victorian depths of his feeling works on us, because we experience it in time with the character. Our glimpse of his unrequited love is mostly limited to one scene: a very British reaction shot when she hugs him goodbye before departing with K-S. Were this film being, lord forbid, remade as a Netflix series, we’d have about six scenes of him moping about while Britpop plays on the soundtrack, plus an exchange of dialogue between two of his friends like:

Can you believe he let her get away? He loved her the whole time and he let his friend marry her!

Damn.

The two friends become estranged not over a woman but by the aftermath of the First World War (in which both men fight), wherein K-S, as a high-ranking officer, is taken prisoner by the British. And in his humiliation he receives Blimp coldly, telling his fellow officers thereafter how little the two nations understand one another. With the rise of Nazism, the now-widowed K-S, who remains an honorable German of the old school, flees to Britain, where he is reconciled with Blimp, who brings him into his household. Together they watch the coming war with trepidation. And though Blimp assumes he will soon be called back into service, he is relieved of his command following Dunkirk. It falls to his German friend to explain it: his adherence to outdated ideas of honour, and his preference for defeat over victory by dishonourable methods will cost them the war against Nazism. He joins the Home Guard as a result bringing us back to the start of the film.

In the film’s denouement, Blimp stands outside his home, which has been partially destroyed in the Blitz, saluting the victorious contingent of the guard as it passes by: a simultaneous recognition of the enduring qualities of Blimp’s Englishness and a gracious passing of the torch to the modern age.

Same guy

What It's Really About

I saw a film today oh boy…the English army had just won the war...

Remarkably the British hadn’t yet won the Second World War during the filming and release of Life and Death, yet one wouldn’t know it from the film’s magnanimous vision. In fact, it was commissioned as a kind of mild propaganda: a (probably redundant) message to British viewers that they were fighting a new kind of war, and they no longer had the luxury of clinging to outmoded and romanticized views of themselves.

The use of Blimp was thus gently ironic: this somewhat ridiculous figure could no longer serve as a comic personification of the British military. Incidentally, Winston Churchill himself evidently expressed concerns about the impact the film’s production might have on morale. (Though one wonders if Churchill knew how Churchillian this depiction of Blimp really was: not just in his eccentric Englishness and courage and large-heartedness, but his having fought, like Churchill, in both the Boer War and the First World War).

Here’s the thing: I’ve seen this movie several times now, and I’m just about positive that it’s definitely making the exact opposite point. Livesey’s Blimp is an anachronism, to be sure, but one the film is pretty clearly in the tank for. It is impossible for me to read the ending as anything but a plea for England to remain like Blimp: essentially the same into the modern world and above all in the face of modern warfare. Indeed, the entire film functions as the most eloquent defense of Blimpishness imaginable. I don’t mean to suggest that it has something to say about military strategy in the context of modern industrial warfare, or even about the ethics of some of its nastier choices like bombing civilian areas of Germany. Rather it seems to be making a subtle argument for retaining a certain kind of Englishness because of and not just in spite of its inherent ridiculousness, insofar as that ridiculousness is bound up with things like honor and decency and loyalty and fair play and all the rest of it. And it does so by making that ridiculousness enormously appealing and, ultimately, moving.

Moreover, it illustrates beautifully how virtuous behavior can appear both ridiculous and serious at the same time. Dueling over a matter of national honor was ridiculous and brave; becoming the protector of his romantic rival is ridiculous and loyal. Even his excessive commitment to the highly colonial pastime of big-game hunting displays bravery (it actually did back then), but more importantly is revealing of his very human avoidance of the friends whose marriage has wounded him dearly.

Right from the start, we are even taught how to watch this film. The flashback part of the film begins 40 years prior, with a young Blimp carousing with a fellow officer in the same bath, much to the annoyance of a senior officer who upbraids them for their, well, tomfoolery. It is then that we get the story behind their playfulness: the song they were singing was an aria from the only phonograph record available to them during their stationing at a particularly tough front during the Boer War. This minor scene, with its flashback within a flashback, is the film in miniature. The message is there from the beginning: things are not always as they seem. Beneath the apparently ridiculous can lie enormous seriousness of purpose.

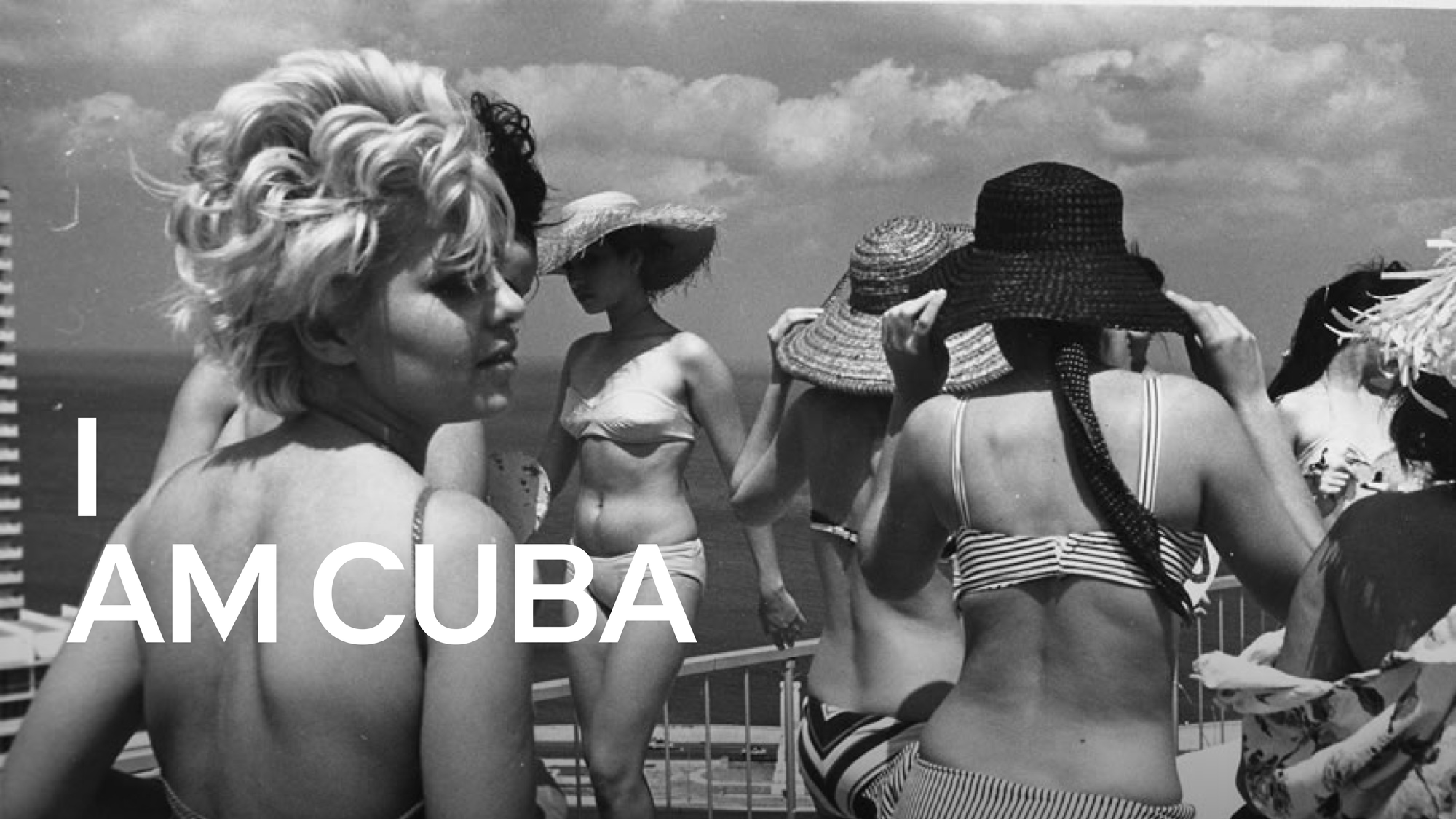

I’m a sucker for movies that zig when they should zag. And I’m particularly interested when there’s a political angle involved. Take Mikhail Kalatazov’s luminous I Am Cuba. It's nominally Soviet propaganda on behalf of the Cuban Revolution, and yeah there’s a sort-of-narrative that follows that thread, but you watch his camera diving into a pool to chase or taking flight over a rooftop cigar-rolling factory, and it’s pretty clear that Kalatazov really couldn’t give a shit about the story. He just loves filming in Cuba. (No wonder he fell out of favor with his Soviet masters).

Powell and Pressburger, despite being citizens of a good liberal democracy like the UK, also weren’t above making propaganda films. Another film of theirs, A Matter of Life and Death (aka Stairway to Heaven), was in some sense about promoting good Anglo-American relations in the aftermath of the Second World War. But they’re clearly way more interested in romance, theories of the afterlife, good jokes at the expense of both Yanks and Brits, and playing around with Technicolor™. But with Colonel Blimp, I see them not so much disregarding as actively subverting the supposed message of the film. That message supposedly being: we’re in a new kind of war, fighting for our very existence against an unscrupulous enemy; traditional schoolboy notions of honor won’t play anymore. Blimpishness is out of style.

There’s a wonderful exchange at the outset of the film that sets the stage: the Home Guard, in which Blimp is a Major-General, is undertaking a training exercise, and in the interest of verisimilitude his opponents have attacked before the official commencement (“like Pearl Harbor”). When Blimp is captured in the Turkish Bath, where he’d been relaxing, and realizes with outrage that the commanding Lieutenant on the opposing side has taken it upon himself to transgress the rules of combat, he splutters: “But may I ask on what authority?” To which the younger man responds, “On the authority of these guns and these men, sir.”

The scene is comic (again, the entire thing is played within a Turkish bath somewhere in London), but this is the heart of Machiavellianism and perhaps, in the end, of politics itself. Yet Blimp will have none of it. And though we are supposed to see the story as one of his acceptance of the new realities of modern warfare, the moral experience of viewing this film is one that inculcates a preference for a praiseworthy national character over mere power worship.

Of course, there is much talk these days among “national conservatives” about restoring a kind of comprehensive patriotism as the basis for stable political life. But such discussions are inevitably generic—they are in favor of the idea of appealing to a given national character without, however, holding a concrete picture of any particular national character in mind. On the other end of the political spectrum, we seem to flee from any positive attempts to characterize the national communities that sustain us, except perhaps by falling back on thin, watery invocations of multiplicity, diversity, and so forth. What we lack are appealing explorations of the phenomenon itself.

That said, the film is not without irony regarding British history but it is a gentle irony — one that records imperial possessions by way of a representative plaque for each major game animal mounted on a wall in Blimps family home (YMMV as to whether you appreciate the gentleness of this irony or find it woefully insufficient). Similarly, his valediction delivered at the news of the armistice for WWI is heavily bowdlerized:

For me Murdoch it means more than that. It means that right is might after all. The Germans have shelled hospitals bombed open towns sunk neutral ships used poison gas and we won. Clean fighting, honest soldiering have won.

Now you know, and I know—and for that matter the filmmakers and educated audience members likely knew—that this doesn’t remotely describe British actions during the Great War, which included blockading the Central Powers into near starvation. (There is also little to no mention during these scenes of the French or American, who might be said to have played a role...)

But by now it should be clear that what is consciously being depicted is not British history but the best English understanding of itself. It is an idealized portrait. They seem to be saying that there is something true in this reflection, that would be made false by too much realism. (Incidentally, Kazuo Ishiguro has credited its depiction of Englishness as a major influence on The Remains of the Day.)

The idealization as one experiences it as a viewer of the film is subtler, however, than I am representing it here. In fact, the only explicit tribute to England’s charms is delivered by the German Kretschmarr-Shuldorff, who praises the countryside with its “gardens, the green lawns, the weedy rivers, and the trees.” It is a remarkably subtle move in a film that is nominally a statement of British nationalism and resolve, that it allows the viewer to see England through German eyes—which in the process humanizes the Germans who are the very enemy against which the British are supposed to be reminded to steel themselves by this film.

I don’t want to make too much of this, but art is always more than one thing. Form and tone matter as much as content, as with, say, Shostakovich’s irony. Or consider how Very Smart People love to point out that “Born in the USA” is in fact bitterly sarcastic…except Springsteen made a clear decision to release the full-band, major-key recording over the solo acoustic one. The performance cuts against the painful story told by the lyrics, such that the overall effect is one of wounded patriotism, not just outright bitterness or disgust (this is pretty directly emphasized in most live performances you’ll hear).

The point is that, as any postmodernist (or Straussian) can tell you: the text is not just the text. The didactic dialogues that bookend the film, explaining why Blimpishness must give way to cold-eyed realism, are not the heart of the story—indeed they are not to be found throughout most of the film’s running time. And, of course, Blimp himself, who is depicted as nothing less than wholly admirable, is not a Machiavellian who sells his soul for his patria. Perhaps even more than his love for three different women, his humanizing friendship (with a German no less) is instead the soul of the film.

I think that soul is most clearly reflected in the moment of reconciliation between the two friends. Blimp himself mostly remains off-screen for the sequence, as K-S in a single unbroken shot explains what has happened to his own country and indeed his own family throughout the 1930s to the unsympathetic diplomatic attachés who must authorize his entry into England. It is a spellbinding sequence, and one of the rare points in which the film addresses the Nazi threat directly. Yet his onscreen audience remains unmoved, and in desperation he appeals for a character reference from the friend whom he had rejected on their last meeting. If you have been paying any attention to the film at all by this point, you must know what’s coming—that Blimp will receive his old friend and forgive his past coldness—but the moment is so beautifully underplayed, and Anton Walbrook (a Jewish actor, incidentally, who is playing a German turning his back on his regime) is so plain and understated in his delivery, and Livesey’s reaction so warm and guileless that I defy anyone not to be bowled over emotionally when it comes.

Perhaps it’s my condition as an aging and sentimental man that I have never been able to get all the way through Colonel Blimp—and especially this scene—without breaking down. Funny and largehearted without being saccharine, a celebration of national character that is somehow purged of nationalist furies even in the height of warfare. If there’s still such a thing as humanism in our degraded modern age, it can be found in this remarkable film.

At the time of this writing, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is available for streaming on Criterion and Max.