Of Conspiracies

C’era una volta, not long after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, I up and moved to Rome. It didn’t take much time for me to view that decision as one of destructive idiocy (invading Iraq, I mean, not moving to Rome). But its causes seemed relatively transparent, if foolish, and it never occurred to me that stupidity in politics required some baroque explanation.

I was surprised, then, at how many of my new Italian friends and acquaintances would—often unprompted—offer highly complex, triple bank-shot type explanations for how we ended up in Iraq, typically involving various configurations of oil prices, the extended Bush dynasty, Zionists, rival factions in the Pentagon, and so on.

All of this struck me as such a violation of Occam’s Razor that, in exasperation, I finally asked one of my colleagues what the hell was up with his countrymen and conspiracy theories. At which point he brought up the anni di piombo, and Operation Gladio, and Licio Gelli and the P2 Masonic Lodge (really), and Vatican sex crimes, etc., and eventually I determined that these were all real things that had happened and not ones he was inventing on the spot.

I suppose it is no accident that the patria of Niccolò Machiavelli—who devoted the longest chapters of The Prince and the Discourses on Livy to the subject of conspiracy, and whose writings are famously shot through with examples of, and even exhortations to, murder, assassination, fratricide, coups, public manipulation, and so on—might produce aficionados of the conspiracy theory. But an interest in conspiracy is hardly the exclusive provenance of Italians.

Indeed, conspiracy theories flourish throughout what Fernand Braudel would call the Greater Mediterranean—not just Italy and Greece, but Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt, the Balkans—and from there well into the Arab world. And, as with Italy, there’s a real where-there’s-smoke-there’s-fire effect here; these theories didn’t emerge in a vacuum.

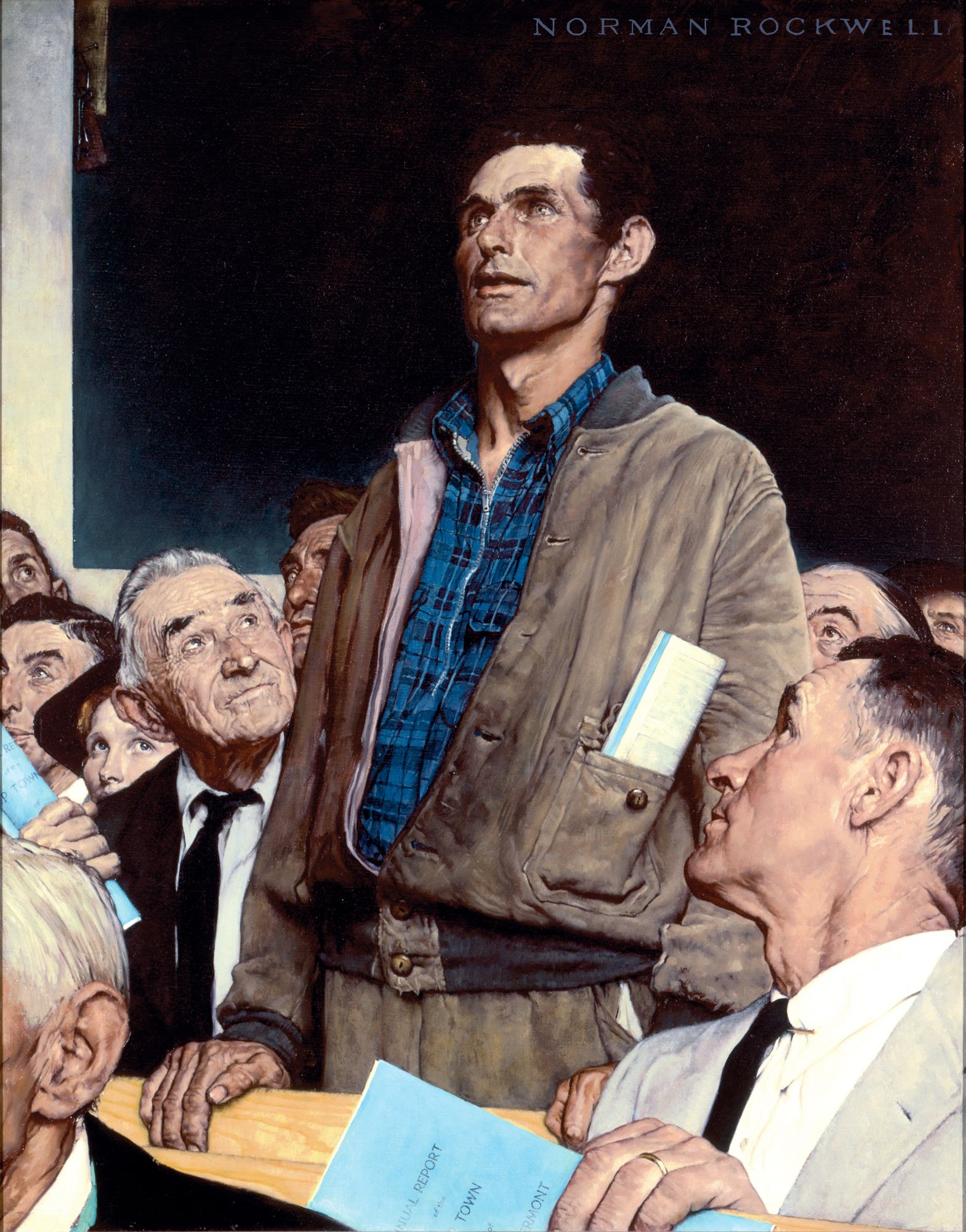

Americans don’t much like this sort of thing. Oh, obviously we have our own set of conspiracy theories, and, historically at least, a healthy suspicion of centralized authority, but still (please don't quote Hofstadter at me). The conspiratorial mindset, while it will always be found on the margins where reality gets thin, is basically alien to the sunny American optimism that is our birthright. That optimism extends to the idea of politics as something that is essentially public. The guy in that famous Norman Rockwell painting isn’t planning an assassination or subverting an election; he’s addressing his peers gathered in assembly. This is how normal politics works, as far as we’re concerned.

Yet since 2016 or so, the theme of conspiracy has re-entered American political life and appears to be here to stay. The last time this sort of thinking took hold in our popular culture was the 1970s, most clearly in cinema: The Parallax View, Three Days of the Condor, Blow Out (technically 1980s, but 1970s in spirit), Chinatown, Marathon Man, All the President’s Men, etc. But these films were very much channeling the spirit of the age—not just post-Watergate, post-Vietnam mistrust of government, but a larger sense of paranoia and violence—the ethos Hunter S. Thompson was mainlining in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. I’m not sure most people know how widespread this stuff became. Everybody knows about Manson and the Weathermen, but these were years when domestic terrorist attacks were a nearly daily occurrence. If we had had social media + the 24-hour news cycle back then, I don’t know that we’d have a country today.

These phantasmagoric visions of conspiratorial politics were basically buried under the Reagan avalanche, and while they never really went away (cf. the Clinton-Vince Foster files), they remained relatively marginalized until November 2016. Suffice it to say, conspiracy is back on the table, but we’re still not particularly good at thinking about it—partly for the very American reasons mentioned above, but partly just because it’s a tricky subject. And it is tricky to talk about because, on the one hand, it is simply too pervasive in the history of political life to dismiss outright; but on the other, there are strong normative conditions that attach themselves to the idea. Conspiracies themselves are clearly questionable, but interestingly so too are accusations against others for conspiring. Consequently, discussions of conspiracy are always politically shaded: both conspiracies AND conspiracy theories are supposed to be something the other guy does.

Moreover, because of the expansive possibilities of conspiracy, it is typically the most colorful and outlandish versions that dominate our understanding of it. Of course, we all have our favorites: David Icke’s Lizard People is highly amusing, but perhaps just a bit too on the nose. I’m personally partial to the “secret history” genre, examples of which include the Tartarian Empire theory (a single global empire built all the beautiful architecture remaining in the world, from the Great Pyramid to Washington’s Capitol Building, before all evidence of its existence was erased); or even better, the New Chronology—endorsed by Garry Kasparov!—(recorded human history does not predate AD 800, and all “Classical” sources are in fact stylized accounts of more recent events).

Over 70 years ago, George Orwell observed that the term “fascism” had ceased to be a meaningful descriptive for a particular political arrangement and had come to mean, in essence, “something not desirable.” I have decided that roughly the same is now true for “conspiracy theorist.” After all, we do not call someone a conspiracy theorist to indicate that they are a scholar who theorizes about the role of conspiracy in political life. Nor, for that matter, do we use it as an equal-opportunity term for those across the political spectrum. Rather, a conspiracy theorist, in the parlance of our times, is a paranoiac, a fool, and above all déclassé. The kind of person who receives and accepts all manner of ludicrous beliefs from the lowest of sources, lacking utterly the intelligence or judgment to sift through the morass of data the modern world presents and preferring to cling to a tidy but absurd narrative.

It’s not exactly wrong either. Ron Unz, for example, used to be a semi-respectable contrarian, publishing The American Conservative and funding scholars like Greg Cochran. Over time, however, you could see him coming around to the idea that anything the New York Times, say, wouldn’t touch is fair game. Which covers a lot of territory? It was, I suppose, only a matter of time before he just started “asking questions” about the Shoah.

Of course, Unz is by now a comparatively marginal figure. If you’re not already ideologically committed to his line of reasoning, there’s little reason to take notice of it—indeed there are strong social barriers against doing so. But I really must stress that in many ways these barriers are social rather than intellectual; it is our animal awareness of social hierarchies and boundaries rather than habits of mind that protect us in such cases.

So what happens when everyone starts to sound like this? When Rachel Maddow on MSNBC and Jane Mayer in the New Yorker and Thomas Ricks and columnist after columnist in the New York Times and Washington Post are pushing the line that conspiracy of some sort operates at the highest level of government, there are no longer any social constraints against thinking in this manner. This is how something like Russiagate becomes conventional wisdom.

But what is a conspiracy anyway? A provisional definition might be: a secretive plot to commit unlawful action against an established political order. And, of course, such things do happen and have happened. Though allowing this opens up the dicey matter of conspiracy theories, something usually thought best left to the rabble. Ross Douthat is one of the few mainstream writers of whom I’m aware to take these seriously, essaying more than one pass at distinguishing between the ludicrous (like David Icke’s lizard people hypothesis) and the plausible (that the official story of Jeffrey Epstein’s rise, fall, and demise is full of holes). Unlike most of his Establishment-type peers, Douthat makes some actual headway by simply acknowledging that conspiracies—and thus conspiracy theories—may have something to tell us about the world we actually live in. But in some ways, I’m not sure he goes far enough.

After all, it is not so easy to disentangle the strands of political life from those of conspirators’ plots. Indeed, the creation of a political society itself often entails elements of conspiracy. As Hannah Arendt remarked, “Those who get together to constitute a new government are themselves unconstitutional, that is, they have no authority to do what they set out to achieve."

It was a conspiracy that gave Athens its democracy and Rome its republic. That same republic fell amid cross-cutting conspiracies (and it was the failure of Caesar’s assassins to fully execute their own conspiracy that resulted in the larger failure to preserve the republic). The Renaissance was a veritable sea of conspiracy—from the assassination of Galeazzo Maria Sforza to the Pazzi conspiracy in Florence etc. (there’s a reason Machiavelli has already made an appearance here).

Nor is this a relic of some bygone era. How much of the 20th century took the shape it did because of the conspiracy to assassinate Franz Ferdinand, thus removing the best chance for a moderate resolution to the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s Balkan Problem—a conspiracy we now know ran straight up through Serbian intelligence?

The point is not to generate some sort of gotcha headline—"How Conspiracy Created the Modern World"—or some other such ridiculousness that might make for a Vox or Slate headline. The point is that the basic modes of conspiracy are bound up with ordinary practice in such a way as to blur the artificial distinctions between public and private life. To disregard this is to miss something crucial about politics.

Matt Levine has a funny recurring bit about how “everything is securities fraud”—i.e., anything that a public company does that is bad, or anything bad that happens to a public company can be interpreted as a move to defraud its investors (from a tort standpoint). Should we say, then, that everything of political import involves some element of conspiracy? Not…exactly? But glancing at the major events in my own lifetime, an awfully large number range from “conspiracy-like” to “definitely conspiracy.”

What, after all, were Glasnost and Perestroika but conspiratorial attempts to liberate the Soviet political economy from sclerosis, while simultaneously attempting to conceal the severity of the crisis from the Soviet public AND attempting to conceal the ambitiousness of the intended reforms from various elements of the Politburo itself?

Since the end of the Second World War, when America assumed a position of near-global primacy, we have interfered in countless elections, overturned governments, trained militaries to act against their own citizens as well as rival countries (but also trained paramilitary groups to act against the militaries of their own countries). Is this conspiracy?

The 9/11 attacks were of course the execution of a successful conspiracy—one whose full extent will probably never be entirely known. And what else would we call the Pakistani ISI’s clandestine protection of Osama bin Laden, while its putative ally sought him all over Central Asia?

Again, none of this requires a secret history. Indeed, it doesn’t even necessarily have to be secret in the moment. If I told you that every year the richest and most powerful people around the planet meet on a mountaintop in the Alps to discuss the business of running the world, you would obviously laugh in my face. But when you read about Davos in the New York Times or CNN.com, you just nod your head and say, “oh yes, of course, Davos.”

Our ability to overlook the obvious when it comes to conspiratorial modes is more common than you’d think. For years and years, Carl Bernstein’s ex-wife Nora Ephron—yes, this Nora Ephron, who wrote When Harry Met Sally and Sleepless in Seattle, and other movies your wife makes you watch—would tell anyone who listened that “Deep Throat” was really former Associate Director of the FBI, Mark Felt. As best I can tell, this had approximately zero impact, and when Deep Throat’s real identity was finally made public following Felt’s death in 2008, almost everybody treated it as a surprise.

That these things happen out in the open is what confuses people. E.g., for a number of reasons, George Soros excites a good deal of attention: he holds enormous wealth; he seeks to use that wealth to foment radical political change at both local and national levels in multiple countries around the world; he channels that wealth through a myriad of often deliberately obscure non-governmental organizations that nonetheless work hand-in-glove with governmental ones to achieve his stated aims; he otherwise channels it toward his preferred electoral candidates at all levels of government in a coordinated strategy in support of those same aims; and so on. Plus, he’s Jewish.

Now much of the above could similarly be said of, say, the non-Jewish Koch Brothers (now just “brother”), though the other parallels here are surely lost on Jane Mayer. Are either of these examples of conspiracy? Well, sort of? These are instances of private individuals orchestrating complex maneuvers to shape the political landscape in ways that surely concern, but are only partly beholden to, the larger public. But again, none of this is being done under cover of night. Whether you obsess about one or the other has more to do with where you fall on the political spectrum than with any coherent ideas about conspiracy in political life.

But if you don’t recognize that a) conspiracy-like practices inhere in “normal” politics, and b) how we view them is heavily conditioned by our own political leanings, you will be totally out to sea when you try to talk or write about it. For example, here’s a much-lauded piece published by the Niskanen Center (an utterly conventional Washington think tank distinguished mainly by its attempts to pretend it’s not an utterly conventional Washington think tank) on the growing right-wing penchant for conspiracy theories. Which goes on to cite as experts Masha Gessen, Jason Stanley, and Sean Illing—every one of whom has backed the utterly discredited Russia-Trump conspiracy theory to the hilt.

For that matter, here is the Washington Post, presently in the process of retracting the very articles that garnered it Pulitzer Prizes, with a helpful quiz to let you know whether You Might Be a Conspiracy Theorist.

Which I guess brings us to our buried lede.

The trouble with the Russia-Trump thesis was not that it involved a conspiracy theory, or even that that particular theory turned out to be mostly wrong. It was that a) the media acted as ministry of information for one locus of political power (the Democratic party) while casting itself as disinterested truth seekers due to its opposition to another locus of power (the Trump White House); and b) they continued to run with their claims well after they had ceased to be remotely plausible, relying upon the fourth estate’s “we have the microphone” version of authority in lieu of actual evidence.

These last two DOJ indictments -- first of Hillary's lawyer, then of Christopher Steele's main source -- show that the Clinton campaign funded and fed to the FBI a gigantic batch of lies in the 2016 election, which the vast bulk of the media spent 3 years ratifying and spreading: https://t.co/Wh0yITrmsl

— Glenn Greenwald (@ggreenwald) November 6, 2021

Indeed, in the process they—as far as we can tell—effectively ended up laundering an actual, if not particularly competent, conspiracy (one executed against Trump rather than by him). Such are the ways that conspiracy and conspiracy theory intertwine. And all of this was of course facilitated by the necessarily undemocratic nature of modern elite institutions: the federal bureaucracy, the most influential media organs, and various non-profits operating as go-betweens for both.

In the absence of direct political engagement—which is always necessarily limited by modern political life—there is a great deal of space for both conspiracies (broadly-termed) and conspiracy theories to take hold. We hear a lot of talk now about the “Deep State” (which originally arose in the context of Kemalist Turkey and was—how to put this?—not all that crazy in that particular context either), but much of what we colloquially refer to as the deep state is simply the state itself. How, after all, can we know that the vast and impersonal and distant organs of government, with their entrenched bureaucracies and alphabet soup of departments accorded enormous powers of surveillance and control all hiding behind the fig leaf that is representation, are in fact operating on our behalf and not according to shadowy designs far from our ken?

In its original incarnation, it was a Turkish phrase—derin devlet—used to describe a literal conspiracy at the heart of Kemalism, In its American incarnation, however, the deep state is really just the state per se. As the modes of political life retreat further out of the public arena and into closed bureaucracies, and as the ambit of state control becomes ever more general, we can probably assume that conspiracy theories will only gain in stature. And this operates dialectically: just as populists will always view elites in conspiratorial terms (the “stolen” 2020 election), so too will elites look to dark, hidden causes whenever populism reaches an unexpected high-watermark (the “stolen” 2016 election).

The challenge for democratic citizens not caught up in this dialectic will be to avoid foolishly denying the way that private modes continue to prevail in political life, without falling down the Ron Unz—or should I say the Rachel Maddow?—rabbit hole. As with all things political, there is no substitute for judgment. Try to keep awake.

PS: But yeah, no way Epstein killed himself.