Tempest in a Teapot, Academic Version

The highly-public humiliation of the Ivy League presidents has prompted many to suggest that we’re finally witnessing the beginning of a sea change in higher education. I think this is mistaken.

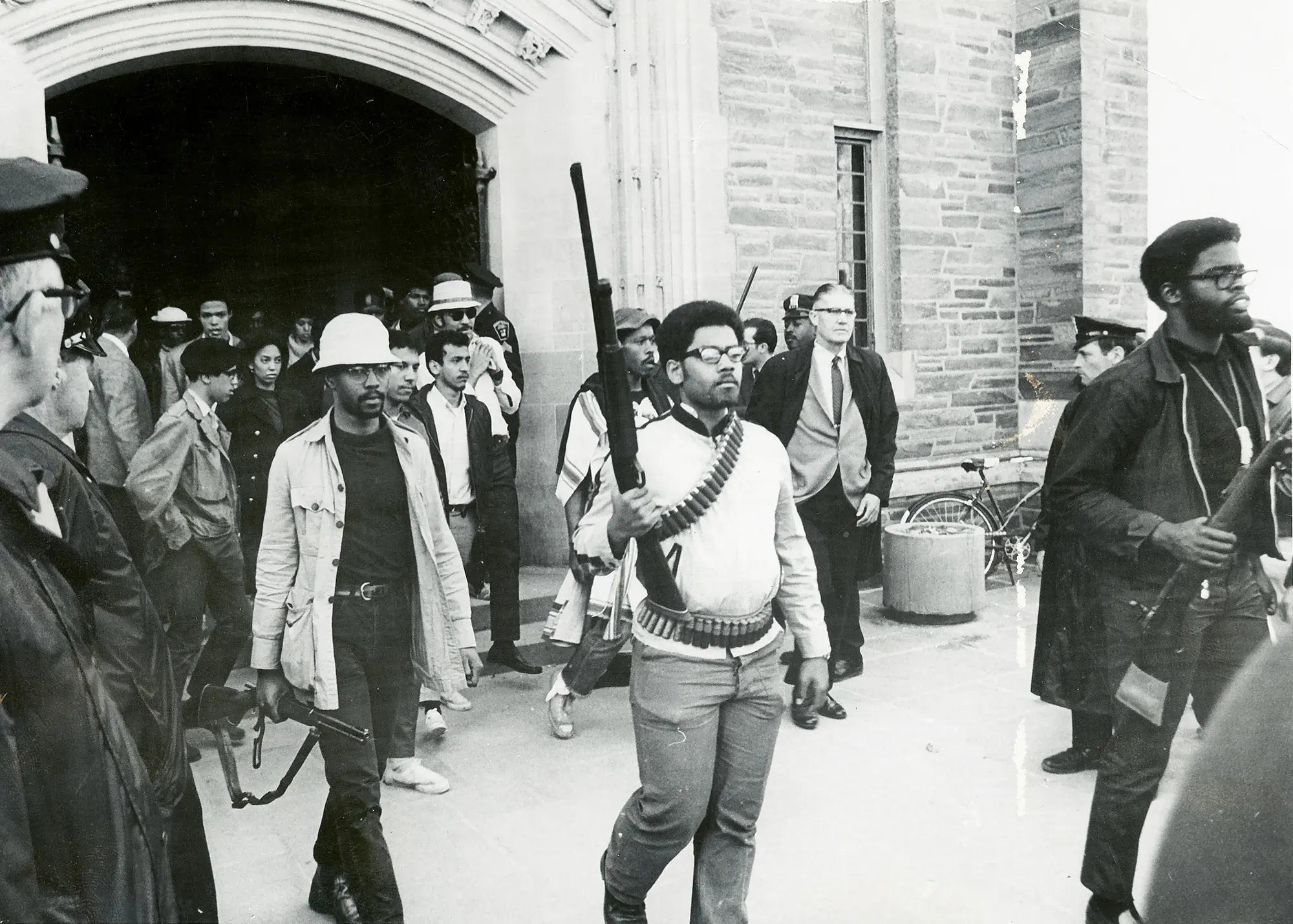

In April 1969, members of the student Afro-American Society moved guns onto the central campus of Cornell University and proceeded to take over the student union building. This represented the culmination of growing radicalism and militancy not just on the highly politicized Cornell campus, but to a large extent in American higher education at the time.

In retrospect, it proved to be one of those strange flashpoint moments that professional irritants like Malcolm Gladwell like to write about. A surprising number of future public intellectuals happened to be teaching or studying there at the time—including Thomas Sowell, Donald Kagan, Francis Fukuyama, and Allan Bloom (the incident served as a major set-piece in the latter’s runaway bestseller, Closing of the American Mind).

None of the campus excitement of the past couple months has come close to this incident in severity or intensity, yet it was these instances of supposed antisemitism that prompted congressional hearings and (at the time of this writing) at least one resignation by the president of an Ivy League university.

The highly-public humiliation of such distinguished figures in conjunction with the generally poor PR academia enjoys these days has prompted many to suggest that we’re finally witnessing the beginning of a sea change in higher education. I think this is mistaken. More to the point, it mistakes some highly visible political agitation for the kind of real structural change that is unlikely to happen as long as our system of mass education remains in place. I’ll explain.

This isn’t getting fixed

Back in 1970 (not coincidentally less than a year after the events at Cornell), Tom Wolfe published one of his more famous (and famously-titled) essays: “Mau-Mauing the Flak-Catchers.” The flak-catchers in his scenario were relatively lowly functionaries of municipal government, whose de facto role was to catch flak (i.e., take verbal abuse) on behalf of their bosses from various frustrated constituents within the inner cities of America. The point is that the flak-catcher exists to allow the people to vent their frustration, without requiring too much to actually happen.

Congress admittedly possesses just a bit more clout than an assembly of lower-income citizens, and thus it didn’t have to content itself with an assistant dean of what-have-you; they could request the presence of the presidents of several Ivy League universities and expect them to duly appear.

Nonetheless, in spite of their prestigious positions and inflated salaries (e.g., Harvard’s previous president pulled down $1.3 million in his final year—a high figure for anyone on the planet but positively astronomical in the context of higher ed), the role they came to play was flak-catcher. And that includes their contribution to maintaining the status quo.

They are now of course furiously backpedaling, as seen by the videos subsequently released, all of which give the queasy impression of watching a struggle session take place. (I am aware, by the way, that there are people who derive an almost erotic charge from watching this sort of public abasement but this should really be resisted at all costs.) These new rounds of public humiliation—which now include not-implausible accusations of plagiarism against Harvard’s president—are just more scenes for the role of flak-catcher.

In any case, not only are these struggle sessions not new; they have become mainstays of our political culture over the past so many years. #MeToo and BLM and various associated hysterias have all provided plenty of opportunities given both the inevitability of transgressions and the incentives for auxiliaries to play the role of punisher.

What has happened in this case is that a sufficient amount of Jewish and more broadly philosemitic outrage was marshaled to bring about such a response, as well as the initial congressional hearing. And it must be said that alongside this was the not inconsiderable influence of (mostly liberal) Jewish donors and philanthropists who only belatedly discovered how uncongenial these institutions had become. All of this is noteworthy because at least in recent years, Jews qua Jews have not featured among the designated identities allowed to claim victimhood. The unexpected emergence (or re-emergence) of this victim class has triggered a fairly hypocritical debate over the importance of free expression in higher education—hypocritical, because the great and good demonstrated little concern for free speech norms over the last few years. But this too is a red herring.

The false promise of neutrality

At this point, it might not be possible to say anything interesting about free speech, but here goes: the importance of freedom of expression is overstated in the public commentary about the state of academia. I am really not trying to be a Yglesias-style contrarian here. Here's an example of what I mean. Psychologist, Harvard Professor, and all around public intellectual Steven Pinker issued a proposal for a return to robust free speech norms on campus in response to both the general clampdowns we've seen over the past few years and the more recent calls to restrict speech associated with violence against Jews:

The wrong way for the elite universities to dig themselves out their reputational hole: restrict speech even more. Instead:

— Steven Pinker (@sapinker) December 7, 2023

1. Clear & coherent free speech policy.

2. Institutional neutrality: Universities are forums, not protagonists.

3. Force prohibited: No more heckler's… https://t.co/aQbjGgxhH3

What classical liberal types like Pinker are responding to here is the blatant absence of a healthy culture of intellectual discussion. And this much is true: serious intellectual debate and inquiry across many areas are constrained by a host of political imperatives. Meanwhile, basically trivial and ridiculous themes–the queering of everything, the diary entries dressed up as social science–predominate; like Gresham’s law of circulation, bad ideas drive out good. And this is without getting into outright fraudulence: the replication crisis; endless p-hacking; pervasive plagiarism, for which the penalties are inversely correlated with status; and so on. And that only covers research! The problems associated with teaching and learning are arguably more severe, but also so much discussed there's little point in belaboring them here.

But insisting on good old speech protections and liberal neutrality won’t wash, because the mission of the university has to go beyond mere liberal neutrality. Think about it: we already have (or are supposed to have) that anyway. What is the value of paying many tens of thousands of dollars a year to enter an institution that merely replicates society at large? Save your money! And defenders of free speech norms, while basically correct on the merits, simply have little to offer, because they haven’t given much thought to what higher education is for.

After all, there is no added value with a place that is basically just Hyde Park Speakers' Corner, only expensive. Certainly, being exposed to a range of perspectives is good, and the echo-chamber quality that results from constricting available political opinions has been much remarked on, especially by conservatives. But this is insufficient, because again the university cannot simply be a bazaar in which the greatest diversity of alternatives finds representation. A History department that also made room for Holocaust Deniers or New Chronologists wouldn’t be very useful, nor would a Chemistry department that allowed for investigations into phlogiston.

The underlying question is not “should students (and faculty) be allowed to run around yelling about ‘globalizing the intifada.’” The question is: why would this happen in the first place? What, in other words, does this have to do with the business of educating young people?

Thus, attempts at some kind of a truce—we won’t punish you for chanting “from the river to the sea” if you stop punishing us for just about everything under the sun—just don’t get us very far. There are two reasons for this. First, the numbers aren’t really there for the kind of mutually assured destruction that would be required to backstop such an arrangement. For example, many are now questioning whether Bill Ackman (and associated parties, one presumes) can marshal both the financial and social capital to basically carve out a Jewish exception to the general anti-white bias of institutions captured by the DEI industry. While I don’t think it implausible for something like this to take hold formally, given both the money at their disposal and what I suspect to be genuine embarrassment on the part of many senior administrators over the highly-public double standard at work, that in itself isn’t sufficient to maintain it.

But second, even if some sort of détente along the lines that Pinker is proposing were really workable, we’d still be back to square one on the question of what a university is for. This is the fundamental question. That protestors have the right to engage in extreme rhetoric is neither here nor there. And that this discussion is even underway is evidence of a collective assumption that education itself is some kind of a right, rather than a good whose value must be assessed in terms of its purpose. As the comparison with the armed Cornell students should indicate, radicalism is not the real issue here: for the students today are not comparatively so radical, and the question at hand is not whether the institutions can properly accommodate them. Furthermore, the average student protestor (yes, even at the Ivies) appears to be vague on just what river and what sea their chants refer to. Geographical literacy has gone the way of literal literacy, it seems.

Again, when one looks back to the post-’68 politicization of the universities, what we are seeing now is fairly tame. After all, the younger crowd today has limited its participation in this sort of thing to sign-waving and social media posts. Recall that 50 years ago, they were actually joining terrorist organizations. Score one for the end of history?

More to the point, the outdated image of academia as an incubator of radicalism is not just passé—it is wrong. For it implies an institution with sufficient independence from the rest of society to be able to exert that kind of leverage over it. On the contrary: it has become a microcosm of society at large. The on-campus demonstrations are no different (and frequently less threatening) than those one finds in the avenues of any major city. The sole difference is that the outrageous cost of the one, along with the pedagogical role it is notionally supposed to perform, invites more concentrated scrutiny.

The point is that these demonstrations, which have nearly always fallen short of actual violence, are not the vanguard of a new revolution; they are merely the political expression of a general dynamic of student life that pervades the university today, and otherwise takes the form of dining halls serving trendy cuisine, state-of-the-art athletic facilities, study abroad programs, and the rest of it. (When I attended Kenyon College as an undergrad, it was common to mockingly refer to it as “Kamp Kenyon.”)

By treating students as customers (which is, ultimately, what they are), universities have inevitably succumbed to the market logic according to which the customer is always right. Thus, allowing them to vent their newfound political ideals regarding Palestine (or, in the case of certain international students, pre-existing ones) is just another form of catering to their whims. Sign-waving on the quad, free condoms, social activities galore—the list goes on. I raise these points not to express offense but to indicate just how far removed they are from the nominal mission of the universities, yet how closely they are coupled to the ever-rising tuition and fees. People want bang for their buck, and until we figure out a way to actually make Lucifer materialize in the classroom, there are just only so many ways you can teach Paradise Lost.

Obviously, the political stuff is likely to generate controversy in ways that a fleet of Pelotons in the gyms is not. And, whether it is obvious or not, the political stuff is hardly new. What is new in this instance is that it has offended—and at least in some cases actually targeted—Jews specifically. Much of the #MeToo outrage took anti-male forms, and much of the BLM demonstrations veered into anti-white rhetoric, but neither males nor whites have a compelling rhetorical appeal to make in this day and age. But, as I have written before, Jews remain a minority, and thus they have a stronger claim to redress under the prevailing value system. Moreover, Jews are disproportionately wealthy (relative to their overall numbers), and not a few Jews are major donors of higher education, who were understandably bemused at some of the behavior their beneficiaries were permitting—and in some cases outright facilitating.

It is this distinctive combination of factors in the Jewish case (and there is almost always something distinctive where the Jewish question is concerned) that has produced a wedge issue within academia after so much prior attention failed to make an impact. The trouble is that the solutions on the table—of carving out a Jewish exception to the DEI framework, or of returning to more robust norms of free expression—don’t get at the problem.

The problem

As it happens, I recently read Peter Brown’s extraordinary memoir, which mostly covers his scholarly career at Oxford beginning after the Second World War (Brown is one of the world’s leading classicists, who has made particularly noteworthy contributions to our understanding of late antiquity, during which classical paganism gave way to medieval Christianity and Islam). His own career spanned the period of politicization and the rise of mass education, yet his primary focus remains the menagerie of first-rate scholars with whom he studied and collaborated. The dominant picture is of the inner world of learning and the mind. It is impossible to imagine figures such as Arnaldo Momigliano or Pierre Hadot or Henri-Irénée Marou joining a mob, whatever their politics. Needless to say, perhaps, this is a fundamentally aristocratic enterprise. Not in the literal sense—for relatively few great scholars actually came from economically or socially privileged backgrounds—but in the substantive sense; for, the students and teachers engaged in this enterprise belong to a self-selecting elite.

It is understandable to view the pushback we’re witnessing on the part of the billionaire class as a reassertion of such aristocratic privileges, but this too is mistaken. Here’s an example. Following the congressional testimony of (now former) president of Penn, Liz Magill, a major donor decided to withdraw his $100 million gift to the school, Specifically, Ross Stevens, founder and CEO of Stone Ridge Asset Management, believes that in light of its failures to uphold protections for its Jewish students, Penn has voided its right to the stock he donated. The purpose of that donation: to establish a center for innovation in finance. Now this is positively Swiftian. Aside from the very real question of whether an already wealthy Ivy League institution is a deserving recipient of charitable donations, one could hardly conceive of a more ironic objective within a place of higher learning than the creation of yet more wealth.

Please understand: I am not at all disdaining wealth or its generation. Like the guy in Idiocracy, I like money. But this is an almost painfully apt illustration of the way that the demands and values of the larger political economy impinge upon the mission of the university. Lazy hacks may continue to employ the phrase “ivory tower,” but it is obvious to anyone who thinks that the tower has been sacked, its walls pulled down and storehouses laid open. For all the routine (and frequently deserved) demonization of the academy, there is really very little daylight between it and society at large. Indeed, this is the final irony: the excesses of the DEI regime and the donor class that has belatedly turned against them are of a piece. Both are primarily driven by varying worldly concerns that are far removed from anything like higher learning. Indeed, the possibility of knowledge for its own sake—or at least as something that gives pleasure and meaning all on its own—has fallen by the wayside. Whether it serves the purpose of what Socrates would have called the “wage-earning arts” or what our contemporary progressives call social justice, the liberal arts and sciences have become instrumentalized.

And while I might personally decry these developments, they are the almost inevitable result of the continuing expansion of mass education. After all, insisting that the university serve the purpose of credentialization for entrants into the market economy had already instrumentalized it. Grade inflation, the campus as hotel and spa, the proliferation of fundamentally fraudulent fields of study, and now the ongoing battle between the faux-radicals and the finance guys—all of it flows from this original development.

To repeat: all of this taken together is nothing more than a system of mass education in a multicultural democracy, compounded by its role as a large-scale credentialing mechanism for a modern political economy. The only solution that will actually be a solution is the severance of higher education from this function. Not the forced resignations of a few high-profile administrators. Not the institution of new free-speech guarantees. Nor even the elimination of formal DEI apparatuses. Like the man said: no more half-measures.